Buyers are unable and sellers are unwilling

September 1, 2014

Published in corporate Gazprom Magazine Issue 9

Polemic

European market at crossroads

After the record-setting 2013 year, Gazprom’s sales keep steadily growing in the European market. Does the current situation in the gas market really satisfy all its participants? The evidence of trouble is the repeatedly occurring conflict about pricing conditions of long-term contracts used by companies from gas exporting countries. Gazprom is no exception here. Just like other suppliers, it is experiencing increasing pressure from its partners who seek to reduce contract prices. Amidst the continuing price revisions often leading to arbitration proceedings, Russian gas sales are growing. By obtaining discounts often coupled with retroactive payments, such buyers go further in their demands and ask for more favors. When one client succeeds in the price reduction issue, the others see it as a guide to follow. The campaign for new discounts which receives full backing of the European Commission and national governments has become a widespread phenomenon endangering stable receipts from gas export.

Let’s try to get the essence of the problem and answer the question: how justified is the demand for price revision? Avoiding turnkey solutions, we propose a range of possible actions that could improve the situation and protect commercial interests of gas suppliers.

Case of buyers

Gazprom’s partners explain the price reduction demand in the following way:

- single, fair and truly market-based price for natural gas has evolved at most liquid European trading platforms (hubs), that is determined by the relationship between supply and demand for this energy resource. Therefore, natural gas has turned into a common commodity like many others;

- oil/petroleum products price indexation as an important tool of the gas industry formation has performed its historic mission. In the new environment the need for it is no longer there, since hubs have formed an alternative pricing center. Besides, the conditions of inter-fuel competition have changed significantly. Petroleum products are no longer used in thermal power generation and can’t be viewed as a natural gas substitute;

- spot prices formed by gas hubs have become a commonly accepted industry indicator of price – a reference point for major end consumers of gas and, therefore, gas importers, i.e. Gazprom’s partners on long-term contracts have to admit it as such as well;

- price wars between wholesale buyers and sellers would never have arisen if the spot and contract prices were not so different from each other. But as a rule, the prices of hubs are lower than those of long-term contracts with a link to petroleum products. This, according to Gazprom’s customers, is explained by the fact that the European market as a whole is facing an oversupply of gas on the back of decreased consumption;

- • by getting gas at prices under long-term contracts and selling it at prices close to the spot level, the importers declare that they get a negative margin from gas trading. This imposes them to ask Gazprom for discounts as well as to demand retroactive payments that would secure backdated compensation for their losses on long-term contracts. The clients propose the ultimate rejection of oil indexation, total and final transition to the pricing based on supply and demand as an alternative to endless revisions of prices.

In reality gas price depends on oil price

Despite the seeming credibility of the image depicted by our customers together with analysts and media servicing their interests, it is pretty far from the reality. The reality is much more complex and multifaceted.

Let’s begin with the assertion that the gas market saw a shift of the pricing paradigm with the emergence of a truly independent alternative price. For many decades the gas price was set there in a unique unparalleled way – through the price of petroleum substitutes. The logic of this, in fact, market-based pricing method is as follows. The gas price is the price which a buyer would have to pay for petroleum substitutes in case of non-delivery of gas in order to attain the equal energy effect (so called principle of substitution). With such exotic pricing structure, the gas demand and supply relationship has no impact on its price which is determined by the dynamics of the oil and petroleum products market with a certain time lag.

On the advancing trading platforms gas prices started to form under the influence of the actual supply and demand conditions, however, these prices were unable to reflect the general market equilibrium in the European gas market, that is, they failed to take over the function which our partners firmly believe them to have. This is explained by the fact that gas hubs are unable to reflect the whole market pattern, and they operate only with residual gas volumes which are in free circulation beyond the supplies under long-term contracts, where different pricing principles are adopted.

As long-term oil-indexed contracts still dominate the market (our estimates put them at above 73 per cent in gas imports in 2013), the movement of spot quotation is mainly based on the prices of such contract. Supply and demand, of course, provoke the price fluctuations around the general trend, but their influence is not significant. In a figurative sense this dependence can be compared to the trajectory of the Earth and the Moon. The Moon’s orbit is mainly determined by the gravity of the Earth, although the Moon, on its part, is able to influence the Earth’s tides.

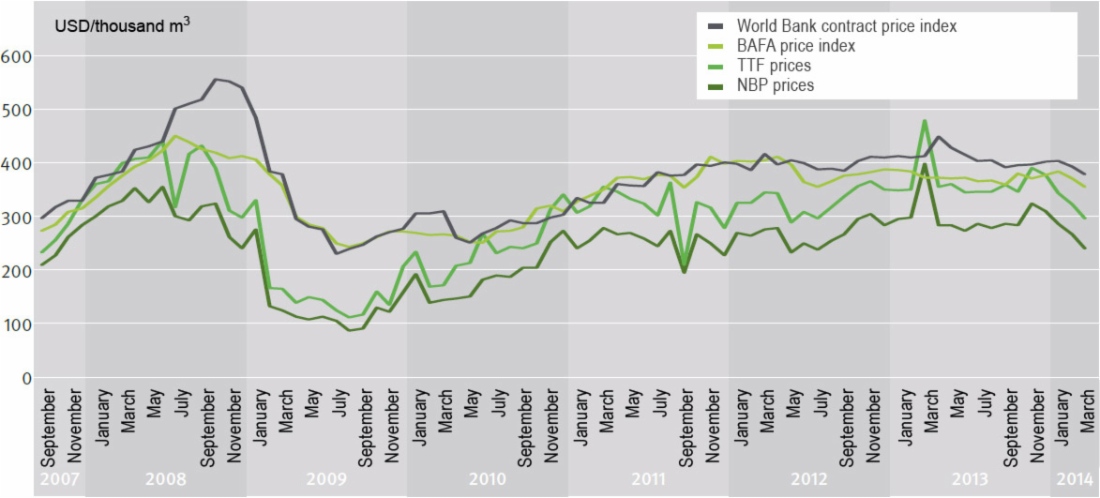

The hub prices are not self-sufficient. They are dependent on the prices of long-term contracts, closely linked to them and move in tandem with them. There is no need to be a gas market expert to observe this dependence (see Chart 1). It’s enough to compare the dynamics of the prices under long-term contracts on the example of two indices: the World Bank’s index and BAFA index, with the prices of the most liquid European platforms, TTF (Netherlands) and NBP (UK). When the prices of petroleum contracts grow, the spot prices follow. The latter also go down unfailingly when the long-term contract prices drop. There is no reason to believe, as do some analysts that stability is an inherent quality of spot prices and that they won’t collapse in case of slump in oil prices. If for some reason oil prices plummet, although there are no indications of it, the gas hub prices will also plummet.

Western experts who claimed that the era of hub-based pricing occurred in the gas market after 2008, including the European one, were puzzled by the unprecedented rise in spot prices in the third quarter of 2010, which, according to all economic theory, couldn’t had happened. The prices rose amidst the sharp decline in gas demand and the Qatari LNG supply glut in the European market. This unexplainable rise in the third quarter of 2010 had, in fact, nothing in common with the balance of supply and demand in the gas market. It was caused by different factors – in October 2010 contracts with end users expired and they rushed to buy gas on trading platforms. Increasing oil prices formed new ceiling prices for these platforms.

The spot prices hike then undermined the financial wellbeing of many partners of Gazprom who firmly believed that the gas market started to exist according to new rules, not oil-indexed. When the prices skyrocketed on the trading platforms, they had already sold the whole of the contracted gas at the forward curve which reflected market expectations for a surplus of gas.

According to our calculations, there is a slight correlation between the Brent oil price and spot prices, but it rises to almost functional dependence (+0.86) in the case with six-nine month moving average price for oil, that is, the analog of a standard long-term contract. Specialist literature provides a lot of studies that carefully calculate the share of market gas sold at different price indexation and also predict the point of no return – release of gas from oil linkage.

But this point hasn’t occurred yet and will not occur until four out of five main suppliers of gas to Europe (Russia, Algeria, Qatar and Azerbaijan in the future) voluntarily give up oil indexation in long-term contracts. Although Norway declared its readiness to transit to spot deals, it’s not enough for the pricing system to be changed. The grounds for retaining the pricing scheme based on substitution are still in force. Of course, petroleum products were abandoned by the European power sector, but the share of gas in this segment accounts only for 12.5 per cent in the EU. The competition between gas and petroleum products is still tough both in the industry and the utility sector. It will only increase as more gas will be used as a vehicle fuel.

Why spot prices are usually lower than contractual ones

The European pricing system could be rightfully called the hybrid system with oil indexation playing a dominant role. However, it’s not enough to say that hub prices are linked to long-term contract prices and, in fact, represent their derivatives. Another specific feature of the existing hybrid pricing system is that spot prices are generally lower than the contract prices. There are two reasons that explain this discount.

Unlike hub-traded gas, contract gas provides for the price premium for reliability and flexibility of supplies. Contract gas here is like renting a car with a driver, while hub-traded gas is like renting a car without any.

Firstly, gas supplied under long-term contracts is an article of higher quality than that traded at hubs, where it is sold by standard lots without any extra services, i.e. delivery to the customer in volumes corresponding to his daily needs. Unlike hub-traded gas, contract gas, being of higher quality, provides for the price premium for reliability and flexibility of supplies.

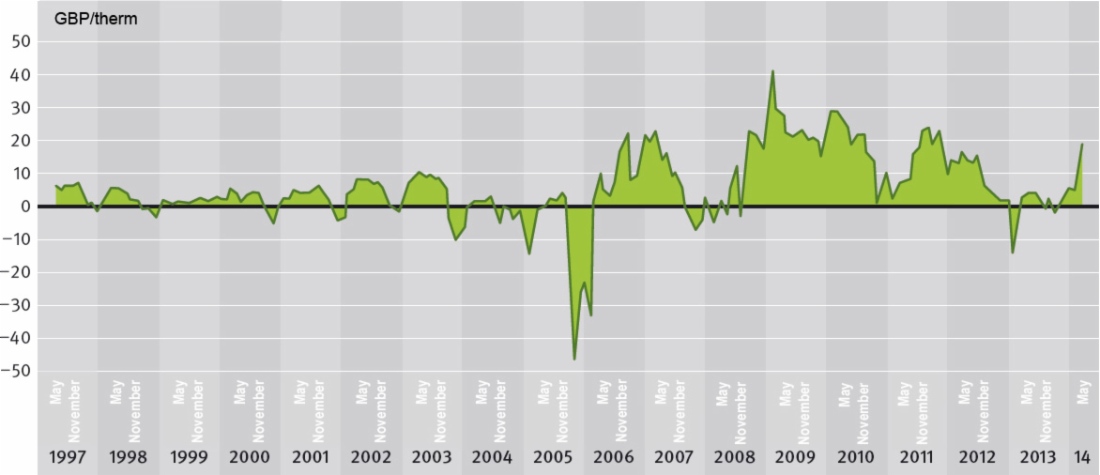

If compared to renting a car, contract gas here is like renting a car with a driver, while hub-traded gas is like renting a car without any. Car rent is apparent to be higher in the first case. In case these rates are artificially balanced, the market will soon recover the price difference. Something of the kind happens after every revision of contract prices when they are balanced with the spot ones (see Chart 2).

According to our model, Gazprom customers’ savings average USD 36 per thousand cubic meters of gas as compared to the parties of fixed contracts thanks to reduction of costs for seasonal stock storage, flexible infrastructure reservation and extended arbitrage operations. Note, there is no unified and generally accepted procedure to assess flexibility, and European customers tend to underestimate its value during negotiations in every possible way, though they seem reluctant to abandon it. Regardless the result of the debates about the quantitative estimation of reliability and flexibility, the market tools solely and independently of the counterparties’ opinion roll back hub-based gas prices versus those of contracted gas by the amount of the abovementioned premium.

The second reason for the lower prices is structural, inherent to hubs only, persistent excess of supply over demand. As mentioned above, long-term contract prices for petroleum products set the general price level for hubs. However, it doesn’t prevent spot prices from fluctuating up and down depending on the supply/demand ratio at these hubs. Spot prices may exceed the average contract ones just for several days due to extreme market conditions (abnormal cold, accidents and etc.), while mostly hub prices stay below the contract ones. The margins of such fluctuations often go beyond the premium for reliability and flexibility of supplies. The PIRA analytics company chart (see Chart 3) shows these system fluctuations.

The transiency of periods when hub-based prices exceed the contract ones stems from the fact that persons receiving gas under Gazprom’s long-term contracts, being entitled to nominate gas volumes, instantly grasp at any possibility to make money out of arbitrage operations. They exaggerate demand for cheaper contracted gas and resell it at liquid hubs, resulting in soonest price balance.

Structural oversupply is possible due to over-contracting of the European gas market (not to be confused with excessive gas volumes). Over-contracting means that the total fixed liabilities of suppliers significantly exceed the actual gas volumes to be consumed.

Structural oversupply is possible due to over-contracting of the European gas market (not to be confused with excessive gas volumes). Over-contracting means that the total fixed liabilities of suppliers significantly exceed the actual gas volumes to be consumed. Liquid hubs development allowed wholesale customers to sell whatever contract volumes at the forward curve for several years ahead, including unclaimed surpluses. They widely use this opportunity to hedge positions, fulfill contractual take-or-pay obligations to suppliers and gain profit prior to receiving gas payments from their customers, notwithstanding the absence of agreements with them. If there were a buyer in the market willing to buy Russian gas under the contract for 2035, this gas would be sold right now.

According to some of Gazprom’s partners, Russian gas (fixed supply liabilities of Gazprom) is resold three to four times before coming to the customer. Gazprom’s partners lack motivation to maintain the balance between spot and contractual prices, because profit shortfalls from such sales would be eventually covered by repayments of suppliers.

Gas excess would not have happened if there had been no liquid hubs. The companies had no chance to escape such excess, but flaring gas. Gazprom’s partners demanded as much gas as their end consumers required or as needed to maintain the seasonal stock. In case the partners were faced with take-or-pay liabilities, the contracted volumes unclaimed during the current year were transferred to the next period (‘makeup gas’) after the relevant partial prepayment had been made.

Relying on their seasonal demand forecasts, gas importers sold the 2014 gas volumes months ago, but they couldn’t be aware of the abnormally warm forthcoming winter; therefore, they couldn’t predict a sharp fall in gas demand, i.e. 56 billion cubic meters (19 per cent) compared to the first half of 2013. Ultimately, gas hub traders (long position holders) had a surplus of natural gas which pushed down gas prices to USD 250 per one thousand cubic meters.

It is believed that the slump of prices is totally the fault of greedy traders selling for a fall. Indeed, traders can push the prices in one direction or another; but the subject they are dealing with is highly sophisticated and unpredictable for gambling, and quite often its behavior differs from the behavior of normal prices. According to our data, actual prices during winter months – 461 out of 640 days (72 per cent) between 2008 and 2013 – were lower than forward prices for the winter gas. It means that traders used to make one typical mistake – they always expected the winter prices would be higher than they could be in reality. Unlike buyers, hub sellers found themselves in an advantageous situation when it came to selling gas at forward prices before the ‘winter’ forward deals are closed. After the sellers had sold gas at higher prices, they could later buy it at lower prices for their clients. The profit of Gazprom’s business partners in such arbitrage transactions is not taken into account when the price revision takes place, because it is necessary to reduce the gap between the actual contract prices and spot prices.

It is not correct to believe that an excess of supply over demand on gas hubs means that the European market has a surplus of natural gas in general – trading platforms only partially reflect the overall supply-and-demand pattern. Different price principles apply to the bulk of gas volumes which are not taken into account. Despite the short-term trend of low demand, the current European market experiences great problems with gas supply – these pressing issues are nowadays being solved exclusively through Russian gas supplies. Since the beginning of 2000’s, Europe saw a 80 billion cubic meters decline in domestic gas production and LNG suppliers abandoned the European market as they redirected their LNG cargoes to the premium markets of Asia (see Chart 4).

Here comes the question: is it worthwhile to keep the hybrid pricing model with all its inherent problems – the now-routine revisions that lead to a creeping degradation of export prices and a one-sided accumulation of discounts? This degradation is particularly noticeable under stable or lowered oil price conditions. Will it be easier to agree on the partners’ proposals and put an end to the price dualism by completely rejecting the indexation to petroleum products?

Consequences of pricing change

So, the prices of European spot trading platforms do not reflect the general demand-and-supply balance, therefore, the equilibrium gas price in Europe may turn out to be nothing like customers and sellers think it to be. Under the conditions when the price is determined only by the demand and supply, the price ceiling will be lifted. In the hybrid model this ceiling was determined by oil prices. But the fixation of the lower price limit to the same oil price that provided for general market stability will also disappear. Free price for gas, which is often produced as a byproduct of oil, may have negative impacts, too.

Price instability is an apparent drawback of spot pricing. Oil indexation, vice versa, provides for the price predictability, thus mitigating the risks of long-term investments into field development and gas infrastructure, making it possible to attract project financing even when the investment horizons make up 30 to 40 years.

Pricing based on demand and supply will not protect against price erosion. In the context of the European market over-contracting, existing flexible contracts providing for the buyer’s right for nominations and separation of contracted volumes sold at the forward market from the actual demand, this erosion will go on, but at a quickened pace. It will not require either complicated price revisions or long arbitration proceedings.

Under traditional oil-indexed contracts the risks of parties to the contract are well-balanced. Thus, a buyer and a seller shared the price and volume risks, and the contracts provided the guarantees of reliable demand and supply. Within the existing hybrid pricing system the buyer’s obligations grow yet more indistinct. Moreover, in case of a full gas indexation, they simply disappear and all risks are shifted to the exporter who is under the obligation to supply gas in all conditions. As for the take-or-pay obligation, the most valuable balancing element in the contract structure, from the seller’s point of view, – it loses its economic significance, because a buyer can dispose of any excess volume of contracted gas on hubs with no risk to his revenues, but causing thereby a new round of price erosion.

The logic of price formation based on demand and supply suggests that the market participants should freely control both the demand and supply volumes. It should be pointed out that this liberal approach in the gas industry often contradicts the necessity to secure the uninterrupted gas flow to supply strategic and vitally important areas of activity.

In the context of new pricing conditions, the price erosion may be stopped only by means of their total restructuring into contracts with unfixed obligations like LNG supply contracts. Thus, each and every long-term contract for LNG supply to Europe, with a link to hub prices, allows the supplier to redirect gas volumes to markets with higher prices. As a rule, fixed supply obligations apply only to a small part of contracted gas, for example, winter supplies. It is not easy to achieve an agreement on such restructuring with our partners as far as pipeline gas is concerned. Actually, it will mean the cessation of supply rather than redirection in case a seller is not comfortable with the price. But even if the talks are a success, it doesn’t guarantee the relationship harmonization.

Transition to spot prices involves extra risks for Gazprom, as it turns the Company into a predictable price prey for the antimonopoly authorities of the European Union. It is triggered by the absence of a single natural gas price, which, like in case with oil prices, would protect the producer from violent interpretation by the customers of its said-to-be fair level. According to the European politicians, the fair gas price shouldn’t exceed the current US price level, which will provide Europe with the equal competition opportunities with them.

In case the European elites place a geopolitical ‘order’, any actions of Gazprom Group aimed at protecting its economic interests will be interpreted as the dominating supplier’s attempts to manipulate the prices. The actions of the European Union antimonopoly authorities in this respect are predictable: charging multibillion penalties, requiring the access of independent producers to Russian pipeline gas export, total price unification.

Contracts with oil indexation are less vulnerable to antimonopoly authorities’ persecution. In this case the price of contracted gas depends not on demand and supply, but on the formula agreed with the partner. Not a single major natural gas supplier can influence the prices for petroleum products it contains. It doesn’t mean that the European Commission gives up its attempts to accuse Gazprom of violating the antitrust legislation. But in order to attain its goal, the Commission will have to prove almost an impossible thing: particular intention of the dominating supplier in concluding a contact with the standard oil formula.

Conclusions

Since the Soviet times Russian gas exporters have pursued the task of building up the sales of this energy source under long-term contracts concluded with national gas companies. The take-or-pay clause as a part of these contracts provided firm guarantees on the part of Europeans to pay for such gas, even if the demand for it in some years were low. Flexibility of supplies that offered a lot of extra advantages to a buyer, was an important means of competitive struggle for European consumers.

It should be admitted that the conventional strategy of building up long-term contract obligations within the agreements with former ‘national champions’, many of which lost their clients in the competitive environment, not only fails to work for the final result, i.e. increasing the export revenues, but can even be counterproductive in the context of liquid hubs. Today liquid trading platforms can absorb any additional gas volumes many months prior to the start of their real supply to end consumers. Larger volumes of Russian gas managed by customers raise the pressure on the price level at trading platforms towards their reduction.

The actual gap between the options on supply and the actual demand has already taken place. Attracting the volumes unrelated to actual demand, the market eventually brings down the spot gas price. This new price then becomes the reference point for reviewing oil prices. Our partners, many of which turn into pure traders more and more, don’t care much about the market over-contracting against the background of problems related to the physical gas availability.

Over-contracting should be eliminated from the market. Customers’ rights to nominate flexible volumes should be limited by means of introducing hundred per cent take-or-pay commitments for contract obligations, which, in their turn, should be brought to the basic load level determined by their customer base.

In summary, with all the credibility of our partners’ image of the present-day European gas market, it differs greatly from the hybrid reality Gazprom has to face. It explains many paradoxes of this peculiar market, such as gas shortage with its simultaneous structural oversupply at hubs; truly market spot prices, which in fact turn out to be a cut-price analogue of oil prices; shaping of our partners’ income or losses owing to the difference between forward and real spot prices rather than by contract and spot ones, the net balance for which is covered by a supplier.

But what has been said doesn’t mean that the hybrid pricing model should be rejected. The alternative proposed by the partners, i.e. long-term contracts with spot prices, is even a less attractive option involving numerous additional risks.

The defects of the existing hybrid market model can be eliminated. First of all, over-contracting should be eliminated from the market. Customers’ rights to nominate flexible volumes should be limited by means of adding a hundred per cent take-or-pay clause to contract obligations, which, in their turn, should be brought to the basic load level determined by their customer base. If trading platform prices represent the industry-wide standard, then it is these platforms, not contracts that should become the source of balancing volumes, making it possible to bring the supply on hubs in line with real demand and stopping the erosion of gas prices as related to oil prices.